Even without a conflict, a comprehensive review of the Indus Water Treaty has been long overdue.

Any honest review of the Indus Water Treaty would show that it has few parallels—rare is the upper riparian state which has such agreements with a lower riparian, and that too a lower riparian state that is relentlessly adversarial.

Therefore, the question that ought to be asked about the Indus Water Treaty signed in Karachi in April 1960 by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistani President Ayub Khan is not whether it needs a review—but how this treaty, brokered by the World Bank, that governs the use of the waters of six rivers in the Indus water basin has survived for so long without one.

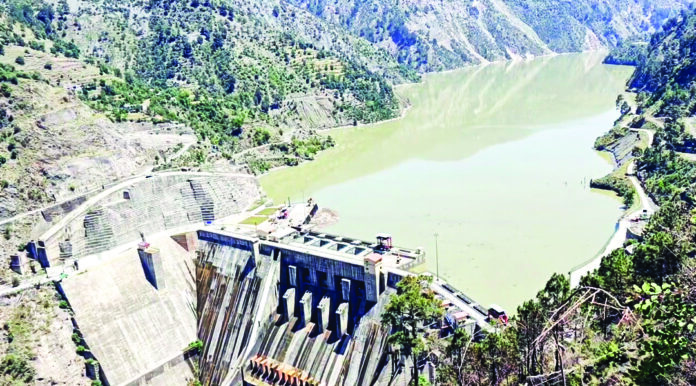

The treaty is remarkable not only because of upper-lower riparian dynamic noted earlier but also because it has survived every conflict, every war between India and Pakistan, as if ensconced in its own bubble. After the dastardly terror attack at Pahalgam, India has kept the treaty “in abeyance” meaning it would not be cooperating with Pakistan on the modalities of the treaty including periodic data sharing, cooperation in controlling water flow and other such issues. It is not widely known in the public square in India that 80 per cent of the waters under this treaty and flows from the three major rivers, Indus, Jhelum and Chenab (western bank rivers), go to Pakistan, and those from Ravi, Beas and Sutlej (eastern bank rivers) are for India. For a long time, India did not even use all the waters in its quota, leaving some extra flow for Pakistan. Part of the reason was also underinvestment in building adequate infrastructure like dams and canals to use the full share which India did not do in the past. But recent developments like the Shahpur Kandi and Ujh dams on the Indian side have caused friction.

Any development of hydroelectric projects by India also causes conflict. The World Bank notes that there is an existing dispute between the two countries on India’s Kishenganga (330 megawatts) and Ratle (850 megawatts) hydroelectric power projects which are on tributaries of the Jhelum and the Chenab and India is allowed to build hydroelectric projects on these subject to some design specifications.

But even without new construction, the ecology is shifting. Profound changes in hydrological patterns, including projected increases in river runoff of up to 27 per cent by mid-century and accelerated glacial melt is threatening a 50 per cent ice loss by 2100, and have fundamentally altered the water management landscape that the treaty was designed to regulate. Demographic pressures have intensified dramatically, with the basin’s population now exceeding 250 million people, causing per capita water availability to plummet from 5000 m³ in 1951 to just 1100 m³ in 2005, with projections indicating further decline below 800 m³ by the end of 2025.

Consider the question of increasing runoffs. The projected changes stand in sharp contrast to the relatively stable hydrological conditions that guided the original treaty negotiations. Importantly, the increased runoff in the Upper Indus will result primarily from accelerated snow and glacier melting rather than increased precipitation, representing a fundamental shift in the basin’s water cycle dynamics. These changes alter not only the quantity but also the timing of water availability throughout the year, with more water becoming available during peak melt seasons and potentially less during traditionally dry periods. The treaty, crafted during an era of relative hydrological stability, lacks mechanisms to address these shifting patterns and their implications for water allocation and management strategies across the basin. The magnitude of these changes necessitates a re-evaluation of the fundamental assumptions about water availability that underpinned the original agreement.

The Himalayan, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush glaciers that feed the Indus Basin are experiencing unprecedented rates of retreat, fundamentally altering the region’s hydrological future. Research indicates that glaciers in the Indus Basin have experienced an average mass loss of approximately 0.2 meters water equivalent annually during the past decade, with projections suggesting an alarming 50 per cent ice loss by 2100. This glacial retreat represents a profound transformation of the basin’s natural water storage system that has historically regulated water availability throughout seasonal cycles. While increased glacial melt initially contributes to higher river flows—potentially beneficial in the short term—the long-term reduction in ice mass threatens the sustainability of water supplies, particularly during dry seasons when glacial meltwater has traditionally supplemented reduced rainfall. The Upper Indus Basin’s future water availability is described as highly uncertain in the long run due to ambiguity in precipitation projections, introducing a level of hydrological unpredictability that the rigid allocation system of the Indus Waters Treaty is ill-equipped to accommodate. This progressive depletion of what scientists often call the “third pole” constitutes a slow-moving crisis that the treaty’s static allocation framework cannot address without substantial revision to incorporate adaptive management principles.

Climate change has dramatically altered the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events affecting the Indus Basin, creating water management challenges unforeseen when the treaty was negotiated. The IPCC projects that extreme precipitation events will increase to a higher degree in the Indus Basin than in neighbouring Ganga and Brahmaputra basins, substantially elevating the risk of catastrophic flash floods throughout the region5. Historical evidence already demonstrates the destructive potential of such events; in 1929, a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) from the Chong Khumdan Glacier in the Karakoram caused flooding on the Indus River 1,200 kilometres downstream, with maximum flood rises reaching 8.1 meters at Attock. The combination of more intense precipitation events and accelerated glacial melt has significantly increased the potential for similar or even more severe flooding events. The treaty contains no provisions for coordinated management of such extreme events or for transboundary early warning systems that could mitigate their impacts. As climate change intensifies, the absence of cooperative mechanisms for flood management represents an increasingly dangerous gap in the regional water governance framework that puts millions of lives and significant infrastructure at risk across both countries.

The physical characteristics of the Indus River system have undergone substantial changes since the treaty’s implementation, altering the effectiveness of existing water management approaches. Research on the Lower Indus reaches demonstrates significant variations in river width (from 2.1 to 12 kilometres) and shifting braiding index values (ranging from 2.11 to 7.18 for the Guddu reach and 2.11 to 4.92 for the Sukkur reach), indicating dynamic morphological processes that continue to reshape the river system. These morphological changes affect water flow patterns, storage capabilities, and infrastructure requirements throughout the basin. Sediment transport dynamics have also evolved with varying compositions of fine sediment and sand. These sediment flows influence river channel formation, flood patterns, and the lifespan and effectiveness of water management infrastructure such as dams and barrages. The treaty provides no framework for coordinated monitoring or management of these morphological changes despite their implications for water resource planning and infrastructure development in both countries. Without accounting for these physical transformations, water management strategies based on the treaty’s original assumptions about river behaviour become increasingly disconnected from hydrological realities.

The ecological systems dependent on the Indus waters have experienced significant degradation that threatens both biodiversity and the ecosystem services upon which millions of people depend. While the original treaty focused almost exclusively on water allocation for human consumption and agriculture, contemporary water management approaches recognize the critical importance of maintaining ecological flows to preserve river health and ecosystem function. The combination of increased water extraction, changing flow regimes, pollution, and climate change has placed unprecedented stress on the basin’s ecological systems. Research indicates that altered sediment flows and changing river morphology have significant implications for aquatic habitats and the species that depend on them. The treaty contains no provisions for ecological flows or cooperative ecological monitoring and management, reflecting the more limited environmental consciousness of the era in which it was drafted. This oversight has become increasingly problematic as understanding of ecological systems and their importance to sustainable water management has advanced. Modern water governance approaches worldwide now incorporate ecological considerations as central components rather than afterthoughts, representing a fundamental shift in water management philosophy that requires a revised treaty framework.

Demographic transformations in both India and Pakistan have fundamentally altered water demand patterns in ways that could not have been anticipated when the treaty was negotiated. When the treaty was signed in 1960, the combined population of India and Pakistan was approximately 530 million; today, the Indus basin alone supports approximately 250 million people, making it one of the most densely populated river basins on the planet. This population explosion has dramatically increased domestic and agricultural water demands throughout the basin. The region has also experienced rapid urbanization, creating concentrated centres of water demand that place additional stress on distribution systems. As a result, per capita water availability in Pakistan has declined precipitously, and well below the internationally recognized water scarcity threshold. This demographic transformation has fundamentally altered the context in which the treaty operates, creating water demand pressures that far exceed those envisioned during its negotiation. The treaty’s fixed allocation approach lacks the flexibility needed to address these evolving demands or to incentivise more efficient water use in response to growing scarcity.

The Indus Basin has become one of the most intensively cultivated regions on Earth, with agricultural practices and water needs that have evolved dramatically since the treaty’s signing. Modern agricultural techniques, expanded irrigation networks, and changing crop patterns have transformed water usage throughout the basin. The Green Revolution, which began shortly after the treaty was negotiated, introduced high-yielding crop varieties that significantly increased agricultural productivity but also required more reliable irrigation. This agricultural intensification has made both countries heavily dependent on Indus waters for food security; any disruption to water supplies now carries potential consequences for hundreds of millions of people. The treaty’s allocation framework was designed for an era of less intensive agriculture and smaller populations, with limited provisions for adapting to changing agricultural needs or technologies. Pakistan, in particular, has developed extensive irrigation networks dependent on the Western Rivers, making the country exceptionally vulnerable to any changes in water availability from these sources. The rigid allocation system established by the treaty fails to create incentives for water conservation or the adoption of more efficient irrigation technologies, leading to ongoing inefficiencies in agricultural water use despite increasing scarcity.

Energy demands have also grown exponentially in both India and Pakistan since 1960, creating new pressures and potential conflicts around hydropower development in the Indus Basin. The treaty includes provisions regarding hydroelectric power generation, that were crafted during an era when energy demands were significantly lower and before modern hydropower technologies were fully developed. Today, both countries face significant energy security challenges, with hydropower representing a potentially clean and renewable energy source in regions with limited alternatives.

All of this points to one immutable fact: even if there were no quarrel between India and Pakistan, the Indus Water Treaty has long outlived its utility, and it is to the benefit of both countries to comprehensively reexamine it.

* Hindol Sengupta is a historian and professor of international relations at the O.P. Jindal Global University.