Perhaps there is a lingering fear that Sanskrit, long presumed ‘dead’ and forgotten, might not be dead after all.

New York: On Tuesday, Tamil Nadu MP Dayanidhi Maran raised the issue of translation of parliamentary proceedings in Sanskrit, a minority language spoken by only 73,000 people, according to him. Translation of MPs’ speeches into Sanskrit, a language that has been declared “dead” by its detractors, may understandably invite surprise or even ridicule. However, the charged animosity displayed by Mr Maran towards a “dead” language is telling. Hardly anybody leads demonstrations against the building of museums or raises slogans to cut the budget of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) on the grounds that they do nothing except perpetuating the relics of the past. Why, then, should the MP single out the government’s minimal expenditure on Sanskrit translations?

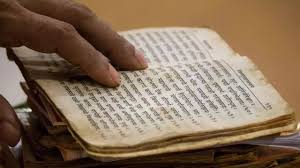

Perhaps there is a lingering fear that Sanskrit—long presumed “dead” and forgotten—might not be dead after all. Perhaps its 3.2 million speakers (first, second, and third language speakers) identified in the 2011 census are rapidly growing. And perhaps the right set of government and private initiatives will revive this language in our times.

Let’s compare Sanskrit to some other languages used for simultaneous interpretation in the Lok Sabha. Remember that Sanskrit is allegedly extinct—so its bar has to be lower than the “living languages.” Besides Sanskrit, simultaneous interpretation is now available in Bodo, Dogri, and Manipuri. Bodo is the official language of the Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR), which sends two MPs to the Lok Sabha. Dogri, which is primarily spoken in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir, is represented by another two MPs. Manipuri, the official language of Manipur, also has two speakers in the Lower House. So, the total number of MPs presumably speaking these three languages is six—a minuscule 1% of the 543 MPs in the Lower House.

Mr Maran claimed that Sanskrit is not the official language of any Indian state. But this is simply not true: Sanskrit is an official language of two Indian states—Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. These states are collectively represented by nine MPs in the Lok Sabha. Thus, at least on paper, Sanskrit enjoys higher representation in Parliament than Bodo, Dogri, and Manipuri combined.

But then Mr Maran might argue that Sanskrit has been artificially imposed by the state governments of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh on their people due to “RSS ideologies.” Let us understand the chronology here. Sanskrit became an official language of Uttarakhand in 2010 and of Himachal Pradesh in 2019. Since the time of these “impositions,” the Congress Party has ruled each of these two states for multiple years. Why, then, did the Congress Party governments not revoke the recognition of Sanskrit as an official language by the prior BJP governments?

Mr Maran also alleged that Sanskrit was not “communicable”—a strange word rarely associated with languages. Does Mr Maran mean that Sanskrit is not a fully developed language with a well-defined grammar, vast vocabulary, and expressive power? If Sanskrit is not “communicable,” virtually no Indian language is, because the standard grammar of almost all Indian languages is modelled after Sanskrit. The oldest extant Tamil grammar, Tolkappiyam, states that it is inspired by the ancient Aindra grammar of Sanskrit. The oldest grammatical treatises on Malayalam (Lilatilakam) and Telugu (Andhra-Shabda-Chintamani) are themselves written in Sanskrit. Does Mr Maran imply that these languages are not “communicable”?

Alternatively, it is possible that Mr Maran meant that Sanskrit was not “comprehensible.” If so, he is incorrect. Sanskrit is comprehensible by those who have learned the language, just as Tamil is comprehensible by its knowers. If he meant to say that Sanskrit is not comprehensible by the vast majority (99%) of Indian people, he is correct. But such a statement is also valid for Tamil, which is not comprehensible by 93% of the country, according to the 2011 census. The contradiction inherent in Mr Maran’s majoritarian agenda on languages is that every Indian language (except Hindi) is a minority language. Large coalitions comprising 90% or more of the population can be built against any Indian language. Does Mr Maran propose that all parliamentary business be conducted only in Hindi?

Mr Maran is also concerned about the wastage of taxpayers’ money on simultaneous interpretation in Sanskrit. However, if his objection stems from the alleged lack of comprehensibility and popularity of Sanskrit, then he should instead welcome the initiative. Investment in the translation of content from other languages into Sanskrit is sure to enrich and popularize the language. Even if MPs do not utilize simultaneous interpretation services in Sanskrit, the voluminous records generated in the process will serve as a future database to train large language models (LLMs). These LLMs are already emerging as powerful tools for fostering the learning and usage of new languages. Our current generation is already the most “Sanskritized” since India’s independence. The next generation is likely to be truly multilingual—switching between languages with ease and dexterity.

From the telecast of parliamentary proceedings, Mr Maran appears to be an avid user of simultaneous interpretation, presumably because he does not understand Hindi—the language used by a majority of MPs. It is not clear if he listens to the English or Tamil translation of the proceedings. However, I hope that he would occasionally try listening to the Sanskrit translation, as it would not only introduce him to a new language but also improve his knowledge of both Tamil and Hindi.

* Kushagra Aniket is an economist and management consultant based in New York, USA. He is also a Sanskrit scholar and an author of multiple scholarly works and can be reached at @KushagraAniket.