Prime Minister’s clarion call to reduce sugar intake by school children is very timely. He emphasised that to reduce intake you need to know how much you are eating. We are talking about prepackaged food products, high in sugar, salt or fats (HFSS). Health Stars might look pretty, but they mislead.

In Australia, where stars have been used for over a decade, evidence shows little to no reduction in sugar or fat content in the food supply. Chile, in contrast, saw a 24% drop in sugary drink purchases within two years of implementing warning labels.

This is why India needs true labels on the front of the pre-packaged food or drink products. After more than a decade of deliberation and over 30 months of delay on a final draft, India now stands at a decisive moment. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has directed the government to finalise amendments to the draft regulation on the Frontof-Pack Nutrition Labelling (FOPNL) within three months.

This is a historic opportunity to empower consumers and protect public health. At stake is how pre-packaged foods and beverages in India will be labelled. Will India “.. undertake necessary amendments in the Food Safety and Standards (Labeling and Display) Amendment Regulations, 2022”? Will the country adopt a Health Star Rating (HSR) system or implement clear, true to its contents warning labels that alert consumers whether a food product is “High in Sugar,” “High in Salt,” or “High in Fat”? This is not a debate about design. It is about truth, transparency, and the right to know. FOPNL is meant to help consumers make quick, informed choices. But under the draft regulation having ‘stars’ on the front of label, unhealthy food products can still receive 2 or even 3 stars.

This happens because the system averages nutrients, masking excessive sugar, salt, or fat with the presence of fibre, vegetables, or nuts. The result? A sugary cereal or a salty snack can look deceptively healthy and throw in 6–8 teaspoons of sugar in one go. That’s not just misleading, it’s dangerous. In a country where children are increasingly drawn to shiny packets of chips and sugary drinks through aggressive marketing, the real danger lies not in what’s visible but in what’s hidden.

Another flaw in the star rating is that it assumes all pre-packaged food products are somewhere on a healthy spectrum. If this regulation is in place, the food industry may aggressively market and advertise their products as “healthier” by flaunting stars on the packet, while continuing to include harmful levels of sugar, salt, and saturated fat. Add to that ‘misleading visuals’ of real fruits or nuts, which are present in negligible quantities.

Thus, the health risks are concealed, not addressed. If star rating is adopted, a packet of biscuits high in energy/sugar/sodium/ and saturated fat could carry 2 or 3 stars. Otherwise, it should have three or four warning labels. A soft drink with high sugar may receive two stars. A box of corn flakes high in both sugar and sodium might still flash three stars. Worse, stars are often misinterpreted as quality endorsements and approvals.

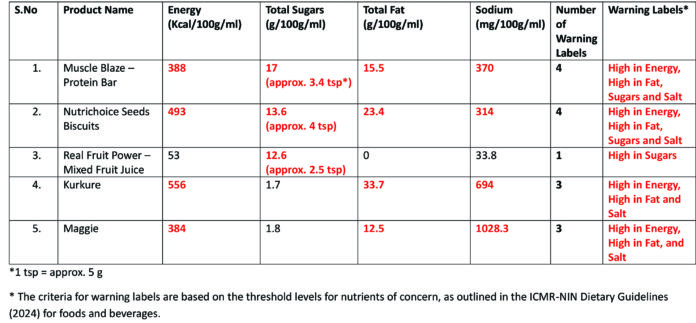

Health Star Ratings may benefit manufacturers, but they fail to serve the public. Evidence from Australia, where HSRs were implemented, shows limited impact on consumer behaviour. Contrast this with countries like Chile, Mexico, Brazil, and Israel, and several others have gone for warning labels. Recent update from the Global Food Research Program at UNC–Chapel Hill demonstrates that mandatory, interpretive nutrient warning labels—most notably black octagonal “High in” icons—are the only frontof-pack system with robust, real-world impact, yielding up to a 24 percent drop in sugary drink purchases. These also led to rapid product reformulation in Chile and Mexico within a year of introduction. India needs a system that is honest and effective. HSR fails on both counts. Earlier this month, the Hon’ble Supreme Court observed: “You all have grandchildren? Let the order on the petition come. You will know what Kurkure and Maggi are and how their wrappers should be. The packets have no information.” This is more than a remark—it is a call to action.

Both Maggi and Kurkure deserve 3 warning labels saying High is Energy, Sodium and total fats. In May 2024, ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition launched its updated Dietary Guidelines for Indians. Implementing it can translate PM’s vision into action. Country’s premier economic survey 24-25 also recommends stringent and mandatory warnings on HFSS or ultra processed food products(UPFs) India stands at the crossroads of a public health emergency and a policy opportunity. The growing “junk food epidemic” is flooding the diets of children with ultra-processed snacks high in sugar, salt, and saturated fat—while industry continues to market them as “healthier” using misleading stars and visuals. On top of it industry is privileged to continue blasting us with their aggressive advertising using celebrities and emotional expressions, without telling the exposed people about the sugar/salt/fat/ energy content of the food product.

In his Mann Ki Baat, Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a simple but profound appeal: “..Children must know how much sugar they are eating, and how much is too much…” This vision must be translated into action. It cannot be realised through star ratings that average out harmful ingredients. It demands warning labels—bold, interpretive, and placed right on the front of the pack—to show clearly when a product is “High in Sugar,” “High in Salt,” or “High in Fat.” or “High in Energy” being expressed in Hindi and or English.

Let us not fail this moment. This would be a great opportunity to educate people how to identify HFSS products for making real informed choices. India must reject the star system and instead notify a regulation that mandates clear, visible warning labels and defines HFSS foods unambiguously. This is not just a labelling reform—it is a public health necessity, a legal imperative, and a moral responsibility to our children. Let us stop sugarcoating the truth. Let our children see the sugar—before it’s too late.

Dr Arun Gupta, Pediatrician and Convenor of Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest(NAPi).